Volume 6, Entry 48: 2ND TRACE

Remembering Mr. Widler

When you frequent the same places for a long time, you start to recognize people.

This makes sense. Every exposure becomes an opportunity to interact, to make a sarcastic remark or roll your eyes and inspire engagement. Connection can spark suddenly, but many people hesitate to reach out until a person is already a known quantity. Familiarity breeds comfort.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about Tyler and how my friendship with him owes to my mother’s grocery store habits, but that’s only one example. I could also point to my morning walks, particularly during the summer. I leave at precisely the same time every day, so I see the same people who follow similarly strict routines. I don’t know these people at all—the older buddies, the woman in the hijab, the grandfather pushing a stroller—but we are all familiars by now. They wave, every time. We share the sidewalks, them and me.

The same thing is true at a high school. With a staff of more than 110 teachers serving 2,700 students, knowing every one of them well would be a tough ask. Teachers connect with their departments and their supervising administrator—this happens organically as they work directly together. And, sure, the right meeting, event, or project can extend a person’s circle, too. But within a school day, there are only so many minutes, and schedules don’t always align. Certain staff members remain strangers.

Of course, other staff members don’t. Even without meaningfully interacting with them, I “know” several teachers secondhand. I’ve taught at least one section of AP Calculus every year since 2011, and that means I’ve taught thousands of juniors and seniors. The vast majority of those students have taken similar courses, meaning I hear a ton about those classes without taking them.

For years, whenever the conversation turned to AP Lang, I knew something: Mr. Bandy was my Honors English 9 teacher. Although I never took the specific class my students did with him, I knew their teacher, so I could take pleasure in hearing my students rave about him as I once did.

Bandy was the exception, though; more often, I’ve heard about instructors without seeing them in action. I recognized Ms. Karl’s projects after years of housing Beloved-inspired AP Lit artistry in my class. I knew about Mr. Siemen’s cats and birthday shenanigans from his Physics 2 students, and the wide heart of Mr. Weinstock from those who took AP Psych. How could I not? So many of my students took so many of their classes before, during, and after mine. Their teachers’ names came up. By osmosis, I learned how Spickelmier ran AP Bio and the jovial storytelling of Mr. Forbes.

But no teacher shared more students with me than Mr. Widler, the inveterate AP Chem teacher. While most of my students took AP World and Lang, nearly every one took AP Chem, the first access point to honors-level science at our school. From those who took his class, I learned about his class. I learned about the content when they explained it to younger peers and about its organization when they said mine resembled his. Year after year, cohorts talked about learning so much from Widler.

During the late 2010s, they twice convinced me to sit in on his class every day during my prep. I didn’t take AP Chem during high school and had an uninspiring experience in that key science course, so I agreed it would be fun to learn from the same guy as everyone else. Alas, my respective back health and workflow changed, COVID closed classrooms, and then Widler retired in 2022. Unlike tens of thousands of students, I never got to take Widler’s class.

Two weeks ago, I received a text message from a former student. That student let me know that Mr. Widler had died. Widler seemingly struggled with his health near the end of his tenure, losing his booming voice, but he was young. His passing was a shock.

After informing my principal, I learned that Widler’s family requested a delayed announcement. Although I talked to two people before getting those instructions, I honored their request by keeping his death to myself. I didn’t write about it or discuss it outside of messages that found me.

Yet I thought about Widler a lot across the weeks that followed. We hadn’t kept in touch after his final day on campus, after all, and I didn’t know him well anyhow. But again and again, I kept coming back to Mr. Widler. Several times, particularly after former students reached out, real emotion found me, too. Truly, a part of me felt like I had lost a friend.

I wondered why.

It takes a special person to be able to get a class of 10th and 11th graders engaged in something as technical as chemistry, but that’s exactly what he did. He was a fantastic teacher who genuinely wanted you to succeed and gave you the tools to do so. I relied on what I learned in his class to breeze through chemistry in college.

He was also pragmatic and matter-of-fact, but not in a cold way. When my grandfather died while I was in his class, I asked if I could take the test at a later date since I was grieving. He said no, but not in an unsympathetic way—I had such a high grade in his class that he knew I could bomb this one test and be fine. I did bomb it, but he was right. I was fine. In that moment, he taught me his most enduring lesson: that no matter how hard I try to be perfect, life will inevitably ensure that I can’t be, and that is okay.

I hope he knows how many people love and respect him. May he rest in peace.

~ Anonymous, Class of 2017

Widler and I taught in separate buildings, but I passed through his classroom on occasion, delivering passes or dropping off permission slips. Whenever he saw me, he always seemed excited, roaring a greeting my way.

Far more often, I bumped into Widler heading to the bathroom. His classroom faced away from the math buildings, so he tended to use the facilities by the theater, and my refusal to wait outside the high-traffic P-wing pair led me there as well. Some weeks, he and I were in sync, chatting while we walked over or back.

These were wholesome conversations, often about a student we’d both taught; he’d ask me how they were doing in Calc and then wax about their triumphs throughout Chem. He remembered everybody, but especially my brother, whom he asked after or offered his best for to close every conversation.

During the beginning of my career, before students wore out a path between our courses, we talked in a different context. His son was a slick-fielding first baseman for another high school in the district, but we only faced his squad once in the preseason during my first year as co-head coach. Although we went on to win the league championship, his son’s squad crushed us 12-3 at home, and Widler came out to watch.

After the game, as I dragged some equipment back toward my classroom, Widler chased me down and offered some encouragement. Frankly, I didn’t want to hear it, but the man’s earnestness kept me from being grouchy. He meant well, and he knew plenty—he’d coached for a while, too. Over the years that followed, we talked about baseball when our bathroom visits aligned. I heard his optimism when his son’s junior year was quiet; I saw him beam as he recounted his son’s latest exploits during a superb senior season.

The longest conversations I ever had with Widler were at the same event every year: the now-defunct Distinguished Scholar awards. Every year a student chose me, a different student chose Widler, which meant we chatted outside Chevy’s or conversed throughout the lengthy ceremony in the performing arts center across town. Widler always bought and wore a tie to match his student’s college of choice; he was a UCLA guy, if I recall, but he donned whatever colors suited his latest protégé. It was to honor them, he always correctly insisted.

Shibata always visits the retirees during their final day on campus, and I’ve been following his lead. Alas, my plans to say goodbye to Widler fell through in 2022 when I caught COVID, and district protocols kept me home until his final day had passed. That meant my final moment with Widler happened, of course, near the bathrooms. As I headed back to the L-building, he approached. His confident stride had become more of a shuffle, and his voice was hushed beneath his trademark liveliness. He paused for a moment to lament getting old, and then chuckled.

“Been a long road, but a good one,” he said.

I assumed I’d see him the next week to shake his hand. I never did again.

Mr. Widler was my tenth grade AP Chem teacher. He lost his voice, which hindered his performance, but he was determined to teach and help his students. He was even willing to stay after class for me and my friends to study for the AP exam. It showed that being in a classroom felt like home to him.

There was one amazing time when Mr. Widler did a flame test experiment using certain chemicals that changed colors. Everyone was mesmerized by the different flame colors.

I was not one of the students who did well in his class, but Mr. Widler was always there to ask any chemistry-related questions I had. Mr. Widler’s class was where I met my eleventh-grade friends. I wish I had gotten the chance to talk to him more outside of school.

Later on, I took General Chemistry in college. I did well in that class, mostly because Mr Widler’s lessons seemed to click back on me. I was more than happy to help my new friends out, no matter how late I stayed up, because I loved learning and teaching Chemistry to others.

When I was done with General Chemistry I, I decided to apply for a job as a lab assistant in the chemistry stockroom. Eventually, I got the job, and my love for chemistry continues, all thanks to Mr Widler.

~ Alvin Nguyen, Class of 2024

On the morning of the 2008 AP Lit exam, a contingent of district personnel entered my half-empty classroom. With balloons, flowers, and multiple cameras behind him, our now-outgoing Superintendent awarded me one of the district’s two Teacher of the Year awards.

Lots of people know how that went because several students in my second period class didn’t take the Lit exam. Our Morning Bulletin crew recorded it and shot photos, and a VP ran to grab my mom, who was still working on campus at the time. I could go find the video if I wanted. It was a thoroughly documented affair.

What isn’t known to anybody (until now) is what I did the following evening. After lingering on campus long enough for it to get dark, I headed out from my classroom to the social science building one unit over. There, tucked into a corner against the fence, I sat down on a small bench.

That bench was a dedication to Rene Mendoza, a popular history teacher and program advisor. Mendoza received the Teacher of the Year award while working at our school, but he died from cancer while still teaching in 2015. When I received the same award, visiting that bench was the first thing I wanted to do.

Which is odd. Because I didn’t know Mr. Mendoza at all.

Or at least, not in the way I would have used the word “know” back then. I never took his class and never worked with him on a project or team. I knew his voice, could probably still pluck it out from a crowd, I’d bet, but I didn’t know him. I didn’t attend his memorial service. I didn’t know Rene.

But also…I did? Students I knew well talked about him. A great many adored him, raving about his class or the Interact Club he spearheaded, while others begrudgingly respected his lofty expectations. He was the favorite teacher of several students I taught, a man whose name came out with pride because their enduring connection to him was a point of pride for them. In a way, I never knew Rene, but I sorta did Mr. Mendoza. I learned about him from what his students shared about him, their thrills of recognition and winces at rebukes. I got a sense of who he was from colleagues, too, including the two who wrote moving tributes in the guestbook that accompanies his obituary.

I learned enough about him to feel it necessary and important to honor him after my special moment.

On the whole, I suspect part of my sadness in the wake of Widler’s death draws from a similar place. Unlike Mr. Mendoza, I did know Widler, and I do have all those memories of conversations and events we shared. But I didn’t truly know him any more than I knew Mendoza.

But I felt—and do feel—a deeper connection to Widler because of the volume of people around me. Since he was sixteen, my brother has brought up Widler as an icon; I knew the man’s name before I joined the staff. I listened to my students talk about AP Chem with what had to be early-onset nostalgia, reminiscing about lessons and labs and bombed tests as if they were remembering three decades ago rather than three months. The Mathletes I spent the most time with adored Widler; they championed the man who gave 140 thorough lectures across four quarters, equipping them to take a brutal AP exam that almost none would completely nail. Why did we see hundreds of students register for the AP Chem test each year when only a few would get 5s? Because they had that much faith in Mr. Widler. He convinced them it was valuable to take, and so they did. Over and over and over and over.

My emotion makes sense in this context. I’m mourning the loss of a colleague I liked, someone who felt woven into the fabric of a place that’s special to me. I talked to him and respected him; I appreciated him and enjoyed when students used him to compliment my style. No matter who took over his class when it all ended, I knew that future Chemistry students had missed out—they’d missed out on meeting and learning from Mr. Widler.

I can’t ever know the depth of impact he had on his students because I wasn’t one of them. No matter how many times I thought about it, I never sat in his class to perform titrations, master heat transfer, or experiment with colorful liquids. But they did, and then they told me about it, and their affection for him amplified my own.

It says everything that numerous students reached out after hearing about Widler’s passing. They assumed I must have known him well.

Because of them, I kinda did.

I had Mr. Widler as my high school AP Chemistry teacher. He was always enthusiastic about chemistry, and his lessons were organized and clear. He also talked me into joining Science Olympiad, and later, he spent a lot of time talking to me about different science majors and careers that I might enjoy. However, one of the things that I most remember was the phrases he always repeated. “Know what you know,” and occasionally, “Know what you don’t know”. He would go on and on about how it has a lot of meaning, but he mostly talked about how it related to knowing what class material you were good and bad at.

What I didn’t realize was how much his influence would help me develop into a better scientist. Beyond encouraging me to pursue science, his endorsement of Science Olympiad let me experience my first in-depth scientific discussions and troubleshooting which are the greatest essence of working in the scientific field. Additionally, recognizing what you do and don’t know is the foundation for scientific thinking and advancement. Truly understanding what is known and unknown in a given field allows you to isolate specific questions to study, form a hypothesis, and design corresponding experiments.

Mr. Widler was great at teaching the AP Chemistry material, but he was even better at kindling students’ interest and understanding in science.

~ Anonymous, Class of 2008

Since 2012, I’ve taught nearly every lesson using a computer, tablet, and projector. It’s thus fair to call them my most-used instructional tools. It’s been thirteen years, and I’m still using them, after all.

Setting aside that infrastructure, though, it’s the graphing calculator that I’d tab as my most crucial instructional device. While it seems like clunky overkill to a middle schooler, the graphing calculator is invaluable as math courses get harder. By the time a student reaches AP Stats and AP Calculus, the device is vital: it does everything we cannot reasonably do by hand.

While I’m rusty on the Statistical strengths, I know its other capabilities quite well. It’s the graphing calculator that enables advanced analysis, locating otherwise impossible zeros and extrema with ease. It solves algebraic equations graphically, it computes derivatives and definite integrals numerically, and it renders even the most complicated functions intelligible on-screen once you’ve fiddled with the Window menu. It’s incredible how much a graphing calculator can do quickly that we simply cannot.

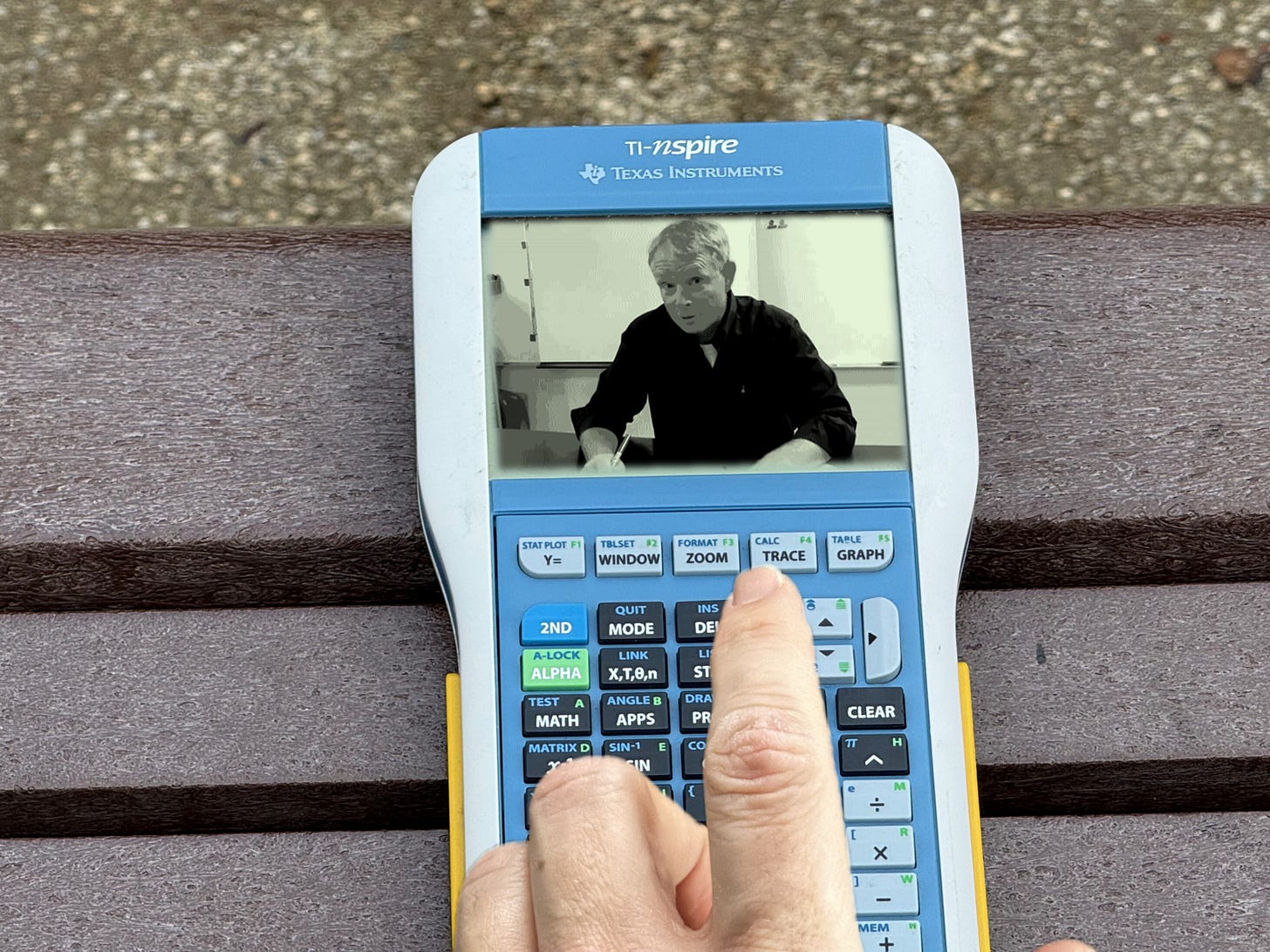

This analytic tool forms the backbone of AP Calculus, and the TI model my students favor houses nearly every valuable operation in the same place. To access that menu, students press 2ND on the left and then TRACE in the upper right. This sequence opens the ubiquitous screen where all their mathematical dreams come true.

In my class, we collectively press that button so many times it’s laughable. Although I favor a different access point for differentiation and integration these days, for intersection, extrema, and zeros, it’s 2ND TRACE forever and always. But amusingly, for more than a decade, my students rarely heard me say “2ND TRACE” within my instruction.

Because I called it The Widler Button.

Mr. Widler’s first name was Trace, like the sum of diagonal elements in a square matrix. Calling the sequence 2ND TRACE felt sterile and mechanical; invoking the Widler Button induced smiles. Every time I said those words—which is to say, his name—a little dose of warmth found my classes. I tapped into a sense of community with my students by alluding to a formative experience for the vast majority of them: AP Chem.

AP Chem with Mr. Trace Widler.

Two years ago, when I taught graphing calculator mechanics to my first Accelerated class, I discovered something odd: they didn’t respond to my Widler Button moniker. They stared at the board, waiting for further clarification, like they hadn’t caught a syllable. The name landed like mathematical jargon to them. It took me a day or so to understand why:

They weren’t taking Mr. Widler’s class; he had retired. My rising sophomores in 2022 didn’t know the man.

It took me a few years, but I adjusted. Knowing that my students would never again take Widler’s AP Chem class, I shifted my language. I’ve called it the CALC menu most of the time or else the CALC button, but sometimes I straight-up refer to it as 2ND TRACE. That way we’re all on the same page.

Perhaps the hardest that Widler’s death hit me last week was when I clicked on the TI-emulator and pursued an intersection point. As I narrated my progression for Accelerated students who hadn’t been using their graphing calculators much lately, my mouse pointer hovered over the blue 2ND key. My mouth formed an S automatically, but my brain pictured Mr. Widler as he was in Gilbert’s music video, seated at his desk in his five-second cameo. My heart dropped. I felt the weight of it all. Widler is gone.

I didn’t feel the loss for me. As I said, I sorta knew Mr. Widler and barely knew Trace Widler. I never took his class or asked him for a rec letter; I never beamed standing next to him with a large plaque, proud to know that my AP Chem teacher would stand next to a younger me on my parents’ mantle for good. He was my colleague—a revered one, sure, and one I got along with easily—but he wasn’t my influential educator. We simply dropped anchors in adjacent docks.

The loss I felt belonged to my students. He nudged them into the sciences, into engineering, into majors, careers, and livelihoods, and they carried the confidence and knowledge he instilled in them forward. They lost a beloved recurring character from their high school stories this month, a man they felt so much affection for that it spread to me, too.

But looking out at my Accelerated class, none of whom ever so much as met Mr. Widler, I felt the sadness more resoundingly. It’s really their loss, and that of the younger peers who back-fill their chairs, that Widler is gone—and not because no one else can do the job but because Mr. Widler did it so well. That I retired the Widler button is just the slow churn of a high school staff, its period far longer than the students’, but equally present, but it’s sad because my not calling it the Widler button for them means Widler will be a name they hear in passing, an odd echo, not a dynamic, kind, and dedicated educator who unlocked the door and turned on the lights to science.

After swallowing down the lump in my throat during that seventh period, I said “2ND TRACE” aloud, but I thought something different. And when I thought of that alternate name, I pictured a man who is gone, who is already mere trivia to the students sitting in his former classroom, but whose influence endures in the hearts and minds of the students and colleagues who admired him.

It doesn’t make sense to call it The Widler Button with my current students, but it does for me. With good health, I will press 2ND TRACE tens of thousands of more times before I follow Mr. Widler out the door, and while the teenagers in my stead won’t know it, I will think of the old AP Chem teacher every time I do. They won’t have known him, but I will, so I’ll do it to honor a man so great at his job that simply uttering his name inspired a healthy buzz. I loved that.

In my head, I’ll keep calling it the Widler Button. I’ll do it for me.

And I’ll do it for Mr. Widler.

RIP, dude.

It doesn’t escape me that this piece about Mr. Widler shares a lot with the thrust of “The Transitive Property” from last week. Both are, after all, about affection for a person that originates from someone else. At the same time, the distinguishing feature here is that I’m not writing about an invented conversation to explain a feeling in my heart this week but using the real voices of people I know and love to express a feeling that’s as much on their behalf as for myself. It’s an odd feeling, but I’m really glad I got to write about Mr. Widler.

I’m so appreciative of Alvin and the others who shared their memories of Widler with me, as well as his other former students who offered. I’m glad the timing worked out for you all to contribute to this piece.

This has been a good week. I’ve gotten a ton done, I’ve slept more than ever, I’ve seen several movies, and I’ve gotten to catch up with numerous people. Rec letters, PIQ feedback, newsletter ideas, artwork—it’s so pleasant to have time and control over the minutes I have. I know this isn’t how the world works, but damn, does it feel good to breathe.

This was a lovely tribute to a truly amazing teacher. Trace was nothing short of an ideal teacher—if I tried to list out the specific qualities I would not do him justice. I can simply say he was a North Star of professionalism. No matter who follows, he set the bar so high that it would be unfair to compare the quality of instruction. To me he is like the Jerry Rice of the Science Dept, simply untouchable in his depth and influence over what a thriving learning environment should be. He is missed, both by staff, former students and as, you so eloquently stated, current and future students who will never know what they missed out on! Thanks again for really thoughtful tribute to a great man!!