Volume 6, Entry 49: Home

A static camera records for ten years

My mom was visiting Minnesota, my brother was out with friends, and my dad was at work. I had the entire house to myself.

You wouldn’t know it because I was talking on the phone in my childhood bedroom with the door closed. The fan above me rattled, and the bed behind me pinned my chair in place, pressing my knees against the ancient wooden desk I’d sat at since second grade.

I was 29.

29.

Surely, I’d outgrown that tiny bedroom years earlier, but my salary had been similarly tiny for so many years that no other options felt viable. Even once my paychecks began to incrementally grow, I kept saving for a future when I would find my own place. I was fortunate to have my financially secure parents cover my room, board, and meals, allowing me to accumulate resources for almost a decade, but this security became a problem. I would have kept right on accumulating if I hadn’t suddenly felt claustrophobic in the only room I’d known for seventeen years and at last understood that I was under someone else’s roof and perhaps didn’t have to be.

I sought out the one real estate agent I trusted, Sue, the mother of a guy I’d coached baseball with. I emailed her right then, with the impression of the desk’s molding still pressed pink into my skin. Three days later, when my Mom returned from her trip, I invited her to look at houses with me.

My decision crushed her, by the way, particularly because I’d made it without consulting her. She tagged along, though, my inclusion her one consolation. Sue showed us seven houses that day, but it was the first one we visited that caught my attention. The small house had been on the market for less than a day, but it already had another bidder eyeing it, too.

Sue worked her magic for me. While Carl, the house’s original owner, was selling his home since 2005, she sold him on me, a local teacher, rather than on that Bay Area investor offering all cash. It worked. Less than one week after being cramped into a tiny box in someone else’s house, I answered a call from Sue en route to the bathroom.

Carl had accepted my bid. I would own his house.

Of course, Sue said “home” when we talked. She always called my future house a “home”. In September, she swung by campus one day and handed me the keys to that house, but she said, “Congratulations on your new home.” After ending the Mathletes meeting, I drove to the place, parked on the driveway, and unlocked the front door.

The place had no furniture yet, and it was two days from being painted, so it was just me and the walls. I stood in the living room for several minutes, silent and unmoving, my feet pressed into the carpet, and then I moved to the kitchen and leaned against the empty counter to behold the space that had suddenly become mine.

It was so…big. Unlike my former bedroom, so much could happen in a room like this. All the dreams in my head could now proceed toward realization right here. I could feel potential surging through my veins. I was excited. I couldn’t wait to fill this place with life and transition into my next chapter.

But amid all that eager anticipation, a different sentiment scratched at my joy. It clawed at me in the kitchen until, at last, it broke through the optimism.

It wasn’t worry. It wasn’t fear. It wasn’t regret. But also: it was all of them? What it was remained a mystery, but why it was there became clearer and clearer as I stared out at the emptiness.

It was because I was alone.

*****

In 2024, two directors released films titled Here. One was an indie romance about moss and homemade soup, and I loved it; the other was an experimental film directed and co-written by Robert Zemeckis, the guy behind Forrest Gump, Castaway, and Flight.

What makes Zemeckis’ Here experimental is its photography: the film is entirely1 shot from a static camera. That camera records the comings and goings in the space that eventually becomes the living room of a New Jersey house. Here follows the families that come to live in that house.

After Here dispenses with CGI dinosaurs and costumed colonial settlers, Zemeckis’ film transitions into a domestic drama. What plays out under his stationary camera’s gaze is life. We watch meals and games, arguments and apologies; we see marriages dissolve and children conceived. Happiness fills the room during one scene only to flee out the unseen back door during the next. We observe the 1950s and 1970s, as well as the effects of COVID-19, weaving us through the years.

At only 104 minutes, there’s not much time for everything Here wants to include and say, and that contributes to what Odie Henderson of the Boston Globe calls “broad acting” and a “cliché-ridden screenplay”. Peter Sobczynski of RogerEbert.com likewise decries it as “cloying and ham-fisted”, valid criticisms considering how doggedly it desires your tears. With that unmoving camera, there’s no straying from what the filmmakers want us to see and take away, and Zemeckis’s screenplay with Eric Roth dispatches with subtlety. Dare I say, Here is so thematically accessible that you might tear up reading the Wikipedia plot summary.

Still, while Henderson calls the film “a bad sitcom”, I find myself willing to forgive a lot of its flaws. I’m a sucker for this kind of schmaltz, notably when it stars the reliable Tom Hanks, and I admire the static camera conceit and the messaging it nods toward regarding intersection and the passage of time.

Primarily, though, I respond to Here because of its perspective. On my first watch, I started the movie while cooking in my kitchen, which sits behind my living room, in a layout that resembles the one I saw on-screen. That odd alignment left me watching that static shot from roughly the same position in my house, forcing me to contemplate not just the Hanks-led drama streaming on Netflix but the drama playing out in the parallel space of my own living room.

Or should I say: the lack thereof.

The fascinating thing about Here for me is how it so effectively captures, over and over again, the domestic drama I anticipated when I first reached out to Sue about buying a house. The visions that played in my head in 2015, that had played in my head for years prior, resembled what Zemeckis put on the screen. I imagined my life centered around a living room of board games and dancing and snuggling and petty spats resolved off-screen. Children ran across the carpet, first clumsily and then confidently, and then, much older, they sat down and scratched away at homework on lap boards. There was no outward window like in the Here house, but there were all the other fixings of livelihood as people came and went, growing and growing older. Even the decay Here showcases had always been a part of my fantasies. I imagined I would decay, too, that I would drop anchor for good in whatever place Sue found for me, wrinkled and worn by time but in tandem with others. The heart of my home would not be a literal fire but the warm presence of others shedding skin cells into the dust that surrounded me.

Here takes place across centuries, but it matches what I wanted from those first ten years in my house. As silly as that is, Here plays like this odd, CGI-addled replication of the vision I shared with Sue when I first met with her, the vision I tried to imagine during my first minutes inside my newly-purchased home. I stood in place trying to conjure what my life would look like moving across the next decade, and I had no problem. I felt alone because I was alone, but that was surely temporary. I could see what was to come. I could believe it would all happen right there in my living room on the tan carpet. I could envision it.

Ten years later, I’ve seen that vision realized in that very room.

When I watched Robert Zemeckis’ Here on the TV in my living room.

*****

I try to stay moving all day, but sometimes, I’ll have made spaghetti or rice that I have to eat at my kitchen table. Since I stand, I look out over my living room like a stationary camera. The angle is almost perfect. I can see the entire room that was my intended hub of life under the roof that has become mine. It’s called the living room, after all. It’s where the living happens.

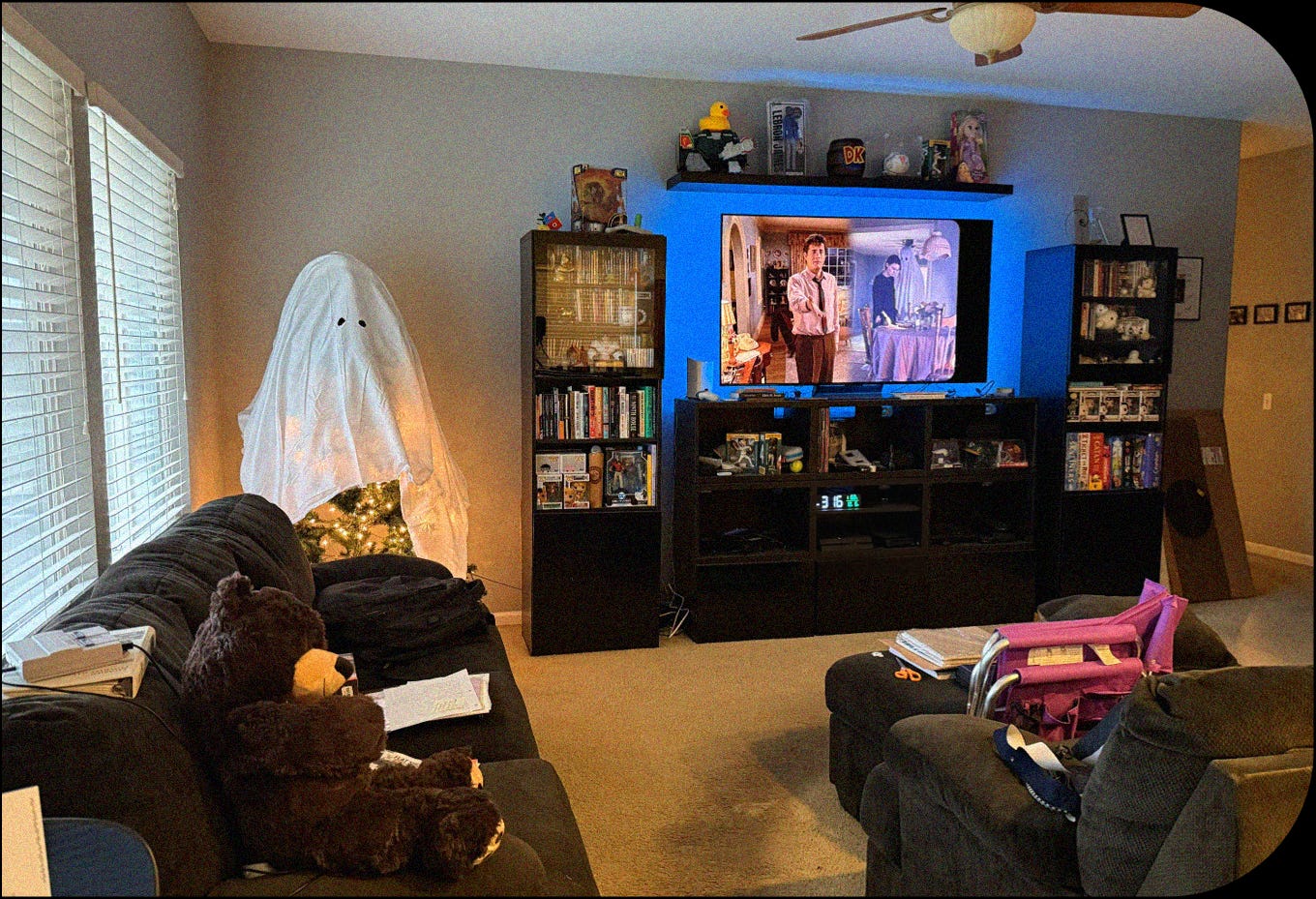

Furniture clutters that room now. Books and movies line shelves that didn’t exist when I stepped inside on September 8, 2015. There’s artwork on the walls and a fridge plastered with cards and photos visible from the sides. Natalie’s and Elio’s cookie recipes hang there, too, just in frame above a magnet schedule for the 2025 Athletics’ season in Sacramento. These are all markers of progress, tangible totems of a house becoming something more. It’s a mess, this place, with paper and equipment and boxes on the couches, but it earns the consolatory compliment that it looks “lived-in”. That’s always been my house’s booby prize. It’s “lived-in”, this place.

Upon closer inspection, a different truth of this place emerges. Pull out a chair, and a thick layer of dust covers the cushioned seat—the couch cushions, too. The throw pillows haven’t moved an inch since the last time someone visited. Whereas my purple yoga mat offers gristle where my planking feet plant each morning, the soft sofas betray disuse. I can look at them and remember precisely where I lay down to watch Your Name on some janky website or fell asleep after a marathon game of Risk ended, but I’ve buried those warm memories underneath a bloated backpack and empty boxes.

If Robert Zemeckis directed Here 2 by replacing my head with a camera over a plate of $1.99 chow mein, what would transpire? What would become the narrative of this space across my first decade in it?

At the start, there would be boxes, too, but the gigantic ones containing IKEA cabinets and bookshelves. Those boxes centered my first adventures in this house because their contents needed to be assembled.

I had fewer back problems then, but still, people took pity on me unboxing an entire house by myself. Five Mathletes offered to help me, and so it was that my first memories of my house were with those five, slowly piecing together wood panels with Swedish screws. Together, we built the furniture that stares back at me from on a carpeted floor not yet matted by 27 million annual steps.

Those couches, although positioned differently, enabled board games and movie nights early on; a mishmash of faces across the years stole white elephant gifts on them and smiled for a timered camera after the first two gratitude dinners. Unexpected people appeared at the door and plopped down on them, including angry, flu-ridden, and apologetic ones; all needed an escape, and my bulging cushions provided one. A few November nights brought out the lap boards for PIQ consultations; the space on the bottom edge of its frame is, amusingly, a registered testing facility with at least one major university.

Those scenes of assembly quickly give way to sustained shots of pain. I lay awkwardly prostrate on the floor playing Yooka-Laylee at 3:30 am because the agony becomes unbearable in bed. Stiff and upright, I sit on the love seat with a thin sheet draped over my elevated legs where persistent throbbing stabs match the rhythm of Satan’s heartbeat, and Gabapentin throttles my brain into mushy ooze. I barely remember what I ate or where I went for huge swaths of my second year here, perhaps because I didn’t do much of either. That’s what we’d watch.

There would also be other moments. Special ones. Bowls of batter Maia stirred through a migraine and mountains of Steeplechase grocery bags Megan and Ethan sorted. An all-nighter revising Teacher of the Year essays with Nate and Bria, and a music video filmed with a lackluster green screen before surgery. Tears shed in this room have soaked into the lint and upholstery—good tears, yes, but also sad ones that certify its safety and warmth. You need a comfortable space to lose a driver’s license throwing cards. You need a welcoming place for Doordashed burgers and chicken wings to parade through and feed two dozen different guests just out of frame on the patio.

Zemeckis would get some silliness here, too. No one’s been experimentally tased inside the house—not inside it—but tasers have been gifted, as have engraved swords and barbecue sets and a giant stuffed Lightning McQueen. And no gift is greater than that of presence, of having someone suddenly appear during a crisis to embrace, to support, to grieve.

Alas, those moments are mere negative space compared to the rest, flashes of life that highlight the gaping rest. Plop Zemeckis’ tripod behind the hearth of my house and watch colossal emptiness whimper to life. Observe as one man narrates PS4 baseball games to a stuffed seal or paces around while lost in the digital world he contains within a 3” by 5” iPhone. Look on while the faces that populated the screen for five years shrink into photographs and warm recollections chilled by an extended winter. Here, Zemeckis’ stage directions would note, a time-lapse sees THE MAN shrinking, but HIS DREAMS OF HOME disappear with his waistline.

It’s bleak in its totality. Henderson would pan Here 2’s “sallow melancholy” and the “wasted promise of a hopeful first act”. Sobczynski would rail against its “reaching for absent emotion” and argue that the static shot “circles loneliness to the point of nausea”. “There’s nothing here”, the podcasters would lament, so disappointed that they’d miss their own pun.

But not the truth. Critics would nail the truth because ten years later, there really is nothing here.

Nothing except me.

*****

There’s another movie that Here makes me think about—a real movie, I mean. It’s called A Ghost Story, and it stars Casey Affleck under a bedsheet.

Directed by David Lowery, A Ghost Story follows C (Affleck), who dies but returns to his former house as a silent ghost. The ghost watches the love of his life (Rooney Mara) grieve, adjust, and then leave before other families take up residence there.

Because Lowery’s script tethers its titular ghost to his former home, A Ghost Story takes place almost entirely in that one location. The camera moves, so it doesn’t use Zemeckis’ static style, yet the film feels remarkably similar to Here thanks to that claustrophobic stage. In both films, the setting traps the audience, forcing us to face only the tiniest slice of life imaginable.

But that’s where the films’ similarities diverge. Whereas Here revels in sentimentality, marveling at the broadly performed lives on its inadvertent stage, A Ghost Story leans into the hauntedness of time’s passage. While would-be Here stories play out, they’re taken as an affront to the deceased. C becomes livid when his wife brings home another man; he rattles the shelves, shatters the plates, and extinguishes the candles to frighten and expel the family who moves in from his house. He’s bitter that the world moved on without him, that it moves on still, that the dreams he had of art and romance and a future have become hollow puffs of air.

There’s a part of me that watches Here and A Ghost Story and sees the story of my house. Zemeckis helms the first five years packed with positive memories and enduring faith in an aging vision, but midway through, there’s a hard cut post-COVID into Lowery that captures the emptiness that took root in its wake. Like Affleck’s former domicile, my house is haunted, but my specters are the ghosts of what might have been. Yes, I can wind the tape and play back dynamic scenes of rich human emotion, but blue blankets everything in a washed-out varnish of possibility squandered.

It went mostly unspoken, but I expected this living room to witness so much more in its first ten years. I presumed there would be a Christmas morning when a little one opened little gifts. That there would be dancing in this room, slow, gentle, and arhythmic. That someone would fall asleep on my shoulder, lost in the comfort of our closeness. And that was the trajectory! That was the point! It doesn’t matter that I have changed, that those images play out on a dusty screen buried under mothballs in a box I’ve tucked into a closet in a different room. Dreams emit a stronger signal than that; the human heart is an organic amplifier. I can erase so much from my paper, with sufficient vigor to make it vanish into rubber shavings that sink under the fraying carpet fibers, but I wrote so, so hard in the beginning. The letters are invisible now, but when you run your fingers over the paper, you’ll feel their impressions. The movie foreshadowed more; how can I blame audiences for wanting it?

When I look out over my living room, I see a man hiding under a sheet. You and I both know who that man is. And we both know why he is here.

[[ Because no one else is. ]]

*****

For a few years there, I used to put up a Christmas tree in the living room. It sat in the corner where I’ve got a lamp and the depleted beanbag chair from Shibata that Ethan and I stuffed with shredded paper. 2019 was the last Christmas I put it up. Naturally.

To this day, when I look out at the room from my spot in the kitchen, I still see the Christmas tree. That is, I can see the space where it should be, or better said, where it could be. There’d be ample room for that tree if I shifted things around, but I don’t. I won’t. The tree dumps plastic needles everywhere, and it’s a hassle to put up and take down. There’s no reason to—

Okay, fine. That was a lie. Those are all valid reasons to keep the tree boxed up at the bottom of my least-used closet, but they’re not why it remains unassembled. I stopped putting the tree up because no one’s coming over anymore. Those Christmas parties I once hosted are relics of the past, scenes from the treacly Zemeckis movie of old, not the somber Lowery flick I’ve got playing in the background now. The tree was put up for the guests, to christen the occasion as festive, to—

Okay, geez. Alright. That was a lie, too. Are you happy now? It isn’t about the parties, and it isn’t because the Christmas tree labor exceeds its value. I loved moving around the living room under the soft glow of that tree. It was beautiful on its own, a beacon of holiday cheer, but it was also lovely because it forced me to think about people.

Megan and Michelle put up the tree with me that first December in 2017. They were excited by the task and energized by the labor, which surprised me after a lifetime of my mom complaining about it. I’d like to think I was helpful, but I definitely played third chair during its assembly that year, a part of me having wandered off into Imaginationland, marveling that I was in my very own house, building my very own Christmas tree. That it was Megan and Michelle putting it up with me added quaint warmth. It was the three of us in 2017, but it would be a different three in 2020 or 2021. 2022 at the worst. This was a preview. This was only the beginning!

But it…wasn’t. In fact, it was just me in 2018 and then again in 2019. That didn’t bother me, but it did feel…wrong? Not because I needed Megan’s help or Michelle’s company, but because it felt like the task was going to become a tradition at some point and then…didn’t. The entire film stopped on a dime in 2020, and then it was over. It became a different movie. A different director. A different cinematographer. A different screenwriter. The camera moved now, too, but more importantly, the costume department draped a sheet over the protagonist and told him to walk around and ruminate on how his memories of putting up the tree that time weren’t a precursor but a climax. The best times happened once and then never again, leaving him to swallow the bitter pill of absence over and over and over until he snaps out of existence in the final shot.

Except.

Except?

Except…

Except that I’m lying again. Or, better put, I’m not so much lying as interpreting this bifurcated film recorded in my living room in the coldest way possible. I’m pulling a Henderson or Sobczynski. Yes, my house is empty most of the time, and yes, I still wince from the impressions left by an abiding but yet-unrealized vision for who I would become, but perhaps I’ve over-prescribed the metaphor. To affix Zemeckis to act one and Lowery onto the second projects an ill-fitting binary onto my past ten years.

Although our Christmas tree in that corner evokes sadness, it also rekindles warmth. Megan and Michelle remain part of my life, each a trusted friend; Michelle will even be here next week to watch the premiere of the Taylor Swift show. The tint of those old holiday memories need not be solely blue. There’s room for red and green and gold. It’s gorgeous screenwriting when a dull corner lights up with generous co-stars. If that was the pinnacle moment, I should celebrate its nourishing echoes and cherish the photos that resurrect it even now.

What Lowery’s ghost misses under his sheet is that he could be watching Here through his ragged eye holes, but instead, he’s wallowing in his own bitter rewrite. When Rooney Mara overcomes her grief and moves on, he boils, but he could instead celebrate her resilience and soak in the thrill of his love returning to a deadened house with life in her heart. That’s pure copium, I know, and that’s not real, but neither is the tragedy he projects onto the human triumphs he haunts away.

In my living room, I’ve helped people get into college. I’ve brought people together and fed them. I’ve hung stockings and watched people I love unwrap gifts. I’ve mourned in here and agonized in here and wanted to die in here, in this very room Zemeckis refuses to pan away from and Lowery refuses to exit from, but I’ve also written scenes of dancing and romance, and I’ve looked over at the couch and seen a friend fallen asleep on the shoulder of her eventual fiancée. I’ve filmed movies and watched let’s-plays, I’ve comforted and been comforted, I’ve told people I love them and had them believe me enough to keep coming back, keep calling, keep reading and listening and texting. None of it is how the original script wanted it, and the Metacritic scores will undoubtedly reflect that weirdness, but if I pull off the fucking sheet and cosplay as Zemeckis’ camera one more time instead of Lowery’s ghost, doesn’t Here have a sequel here? Hasn’t there been enough in this living room to justify the project? Isn’t there still more to come? I swear there’s enough to cut an hour forty from ten years of raw footage.

If I take off the sheet and stop haunting myself here, this house begins to look different.

It maybe even starts to look like a home.

Got a mailbag question? Send it to intenselyspecific@gmail.com.

Mailbag #18

Can you do a personal ranking of the five love languages?

Cheryl from Berkeley

These “love languages” are new to me. Here are my rankings, beginning with my least preferred.

5. Receiving Gifts

Chocolates melt, flowers wilt, and jewelry tumbles down hotel sinks. Gifts cost money, and currency creates a deceptive sense of valuation behind gifts, hence the three months’ salary engagement ring. There’s power in a tangible token that attests to fond feelings, but those trinkets are mere placeholders for the abstract affection they mean to convey.

4. Acts of Service

The “Show, don’t tell” maxim nudges this up the list, but indirectness drops it right back down. Doing something for someone is a lovely gesture, but generosity begets expectations over time. If Acts of Service really does mean doing pesky chores so she doesn’t have to, well, I’d rather prioritize clear communication and explicit requests for assistance than broad swipes at presumed support.

3. Words of Affirmation

Words are my love language, but I’m honest about their limitations. Like many insecure folks, I don’t believe praise—I crave it, but compliments never stick. Words manipulate, words deceive, words write checks that a human heart won’t keep. Love is an inertial reference frame, not an immutable measurement. I have no doubt the road to my heart runs through words, but I’ll always suspect I’m heading into a brick wall Wile E. Coyote painted.

2. Physical Touch

I understand that touch can deceive, that carnal desire can overwhelm enduring affection, that contact can be weaponized and monstrous, that touch is a delicate, terrifying thing. I get it; I really do. But there’s something about physical touch that certifies connection in a way that words only approach. A hand on your cheek says “I trust and adore you” far more convincingly than the words themselves.

1. Quality Time

Yes, physical intimacy transmits a powerful message of affection, but more persuasive than contact, words, service, or gifts is staying close to someone without some activity or exchange in mind. When simply having them present is reward enough—chef’s kiss. To sit silently near someone and feel the universe resolve defines love for me. I suspect it always will.

I recorded a very short audio reflection for the piece. It can be listened to here. I also recorded an hour-long video to accompany it, but it got blocked in 28 nations—including yours. Whoops

This piece is a failure. It never reaches the emotion that I felt while writing it or, especially, while conceiving it. I wanted something grand, a supreme treatise on the view of my living room that acknowledges the ghosts populating it before culminating in a celebratory twist that acknowledged all that has happened there. And…yeah, I never achieved that. “Home” misses both the unrelenting hauntedness of the silence I crave and the profound relief of discovering moments for Here 2 in my memories of living alone. There’s much, much more to say, but I’m definitely going to look elsewhere next week.

As an aside: I really do recommend both Here and A Ghost Story. The latter is a stronger, deeper film, but accessibility has redeeming qualities. Here is available on Netflix; A Ghost Story is rentable everywhere.

The camera moves only during the final seconds of the film.

Ten years ago I was still excepting, hoping, (delusionally so) that I’d be a pro skater. And if that had of happened, I wouldn’t have gone to uni, I wouldn’t have met Evie, and I wouldn’t have started writing. I guess, what I’m saying is I’m glad my expectations weren’t realised.

I’m not saying that’s how you should feel, of course, I just think lots of us are weighed down by expectations we had when we didn’t know any better.

I also think, having watched my parents live together for many years when they shouldn’t have, that just because there are other people in your house that doesn’t mean you want feel alone. My parents are now divorced, and both of them live alone, and they seem far happier like now when they were together.

I also relate to your experience of not putting the Christmas tree up, when I lived alone I didn’t bother with such things. But one of the many things Evie has taught me is that sometimes doing those little things for yourself help in ways that are somewhat intangible.

I apologise if my comment comes across as advice — it’s not meant to.

A very deep and thoughtful piece, Michael. :)

I have missed reading your writing these last few weeks. This is a beautiful exploration of expectations and the strange paths our lives take. I relate to that feeling of haunting your own life and home. I fixed that by getting two cats and eventually Michael.

I hope you put up your tree this year, even if it's just for you. And I hope you can feel at home in the space, even if it's not the home you initially imagined.